Scope of Practice in Speech-Language Pathology

Scope of Practice

Ad Hoc Committee on the Scope of Practice in Speech-Language Pathology

About this Document: This scope of practice document is an official policy of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) defining the breadth of practice within the profession of speech-language pathology. This document was developed by the ASHA Ad Hoc Committee on the Scope of Practice in Speech- Language Pathology. Committee members were Mark DeRuiter (chair), Michael Campbell, Craig Coleman, Charlette Green, Diane Kendall, Judith Montgomery, Bernard Rousseau, Nancy Swigert, Sandra Gillam (board liaison), and Lemmietta McNeilly (ex officio). This document was approved by the ASHA Board of Directors on February 4, 2016 (BOD 01-2016). The BOD approved a revision in the prevention of hearing section of the document on May 9, 2016 (Motion 07-2016).

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Statement of Purpose

- Definitions of Speech-Language Pathologist and Speech-Language Pathology

- Framework for Speech-Language Pathology Practice

- Domains of Speech-Language Pathology Service Delivery

- Speech-Language Pathology Service Delivery Areas

- Domains of Professional Practice

- References

- Resources

Introduction

The Scope of Practice in Speech-Language Pathology of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) includes the following: a statement of purpose, definitions of speech-language pathologist and speech-language pathology, a framework for speech-language pathology practice, a description of the domains of speech-language pathology service delivery, delineation of speech-language pathology service delivery areas, domains of professional practice, references, and resources.

The speech-language pathologist (SLP) is defined as the professional who engages in professional practice in the areas of communication and swallowing across the life span. Communication and swallowing are broad terms encompassing many facets of function. Communication includes speech production and fluency, language, cognition, voice, resonance, and hearing. Swallowing includes all aspects of swallowing, including related feeding behaviors. Throughout this document, the terms communication and swallowing are used to reflect all areas. This document is a guide for SLPs across all clinical and educational settings to promote best practice. The term individuals is used throughout the document to refer to students, clients, and patients who are served by the SLP.

As part of the review process for updating the Scope of Practice in Speech-Language Pathology, the committee revised the previous scope of practice document to reflect recent advances in knowledge and research in the discipline. One of the biggest changes to the document includes the delineation of practice areas in the context of eight domains of speech-language pathology service delivery: collaboration; counseling; prevention and wellness; screening; assessment; treatment; modalities, technology, and instrumentation; and population and systems. In addition, five domains of professional practice are delineated: advocacy and outreach, supervision, education, research and administration/leadership.

Service delivery areas include all aspects of communication and swallowing and related areas that impact communication and swallowing: speech production, fluency, language, cognition, voice, resonance, feeding, swallowing, and hearing. The practice of speech-language pathology continually evolves. SLPs play critical roles in health literacy; screening, diagnosis, and treatment of autism spectrum disorder; and use of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF; World Health Organization [WHO], 2014) to develop functional goals and collaborative practice. As technology and science advance, the areas of assessment and intervention related to communication and swallowing disorders grow accordingly. Clinicians should stay current with advances in speech-language pathology practice by regularly reviewing the research literature, consulting the Practice Management section of the ASHA website, including the Practice Portal, and regularly participating in continuing education to supplement advances in the profession and information in the scope of practice.

Statement of Purpose

The purpose of the Scope of Practice in Speech-Language Pathology is to

- delineate areas of professional practice;

- inform others (e.g., health care providers, educators, consumers, payers, regulators, and the general public) about professional roles and responsibilities of qualified providers;

- support SLPs in the provision of high-quality, evidence-based services to individuals with communication, feeding, and/or swallowing concerns;

- support SLPs in the conduct and dissemination of research; and

- guide the educational preparation and professional development of SLPs to provide safe and effective services.

The scope of practice outlines the breadth of professional services offered within the profession of speech-language pathology. Levels of education, experience, skill, and proficiency in each practice area identified within this scope will vary among providers. An SLP typically does not practice in all areas of clinical service delivery across the life cycle. As the ASHA Code of Ethics specifies, professionals may practice only in areas in which they are competent, based on their education, training, and experience.

This scope of practice document describes evolving areas of practice. These include interdisciplinary work in both health care and educational settings, collaborative service delivery wherever appropriate, and telehealth/telepractice that are effective for the general public.

Speech-language pathology is a dynamic profession, and the overlapping of scopes of practice is a reality in rapidly changing health care, education, and other environments. Hence, SLPs in various settings work collaboratively with other school or health care professionals to make sound decisions for the benefit of individuals with communication and swallowing disorders. This interprofessional collaborative practice is defined as "members or students of two or more professions associated with health or social care, engaged in learning with, from and about each other" (Craddock, O'Halloran, Borthwick, & McPherson, 2006, p. 237). Similarly, "interprofessional education provides an ability to share skills and knowledge between professions and allows for a better understanding, shared values, and respect for the roles of other healthcare professionals" (Bridges et al., 2011, para. 5).

This scope of practice does not supersede existing state licensure laws or affect the interpretation or implementation of such laws. However, it may serve as a model for the development or modification of licensure laws. Finally, in addition to this scope of practice document, other ASHA professional resources outline practice areas and address issues related to public protection (e.g., A guide to disability rights law and the Practice Portal). The highest standards of integrity and ethical conduct are held paramount in this profession.

Definitions of Speech-Language Pathologist and Speech-Language Pathology

Speech-language pathologists , as defined by ASHA, are professionals who hold the ASHA Certificate of Clinical Competence in Speech-Language Pathology (CCC-SLP), which requires a master's, doctoral, or other recognized postbaccalaureate degree. ASHA-certified SLPs complete a supervised postgraduate professional experience and pass a national examination as described in the ASHA certification standards, (2014). Demonstration of continued professional development is mandated for the maintenance of the CCC-SLP. SLPs hold other required credentials where applicable (e.g., state licensure, teaching certification, specialty certification).

Each practitioner evaluates his or her own experiences with preservice education, practice, mentorship and supervision, and continuing professional development. As a whole, these experiences define the scope of competence for each individual. The SLP should engage in only those aspects of the profession that are within her or his professional competence.

SLPs are autonomous professionals who are the primary care providers of speech-language pathology services. Speech-language pathology services are not prescribed or supervised by another professional. Additional requirements may dictate that speech-language pathology services are prescribed and required to meet specific eligibility criteria in certain work settings, or as required by certain payers. SLPs use professional judgment to determine if additional requirements are indicated. Individuals with communication and/or swallowing disorders benefit from services that include collaboration by SLPs with other professionals.

The profession of speech-language pathology contains a broad area of speech-language pathology practice that includes both speech-language pathology service delivery and professional practice domains. These domains are defined in subsequent sections of this document and are represented schematically in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of speech-language pathology practice, including both service delivery and professional domains.

Framework for Speech-Language Pathology Practice

The overall objective of speech-language pathology services is to optimize individuals' abilities to communicate and to swallow, thereby improving quality of life. As the population of the United States continues to become increasingly diverse, SLPs are committed to the provision of culturally and linguistically appropriate services and to the consideration of diversity in scientific investigations of human communication and swallowing.

An important characteristic of the practice of speech-language pathology is that, to the extent possible, decisions are based on best available evidence. ASHA defines evidence-based practice in speech-language pathology as an approach in which current, high-quality research evidence is integrated with practitioner expertise, along with the client's values and preferences (ASHA, 2005). A high-quality basic and applied research base in communication sciences and disorders and related disciplines is essential to providing evidence-based practice and high-quality services. Increased national and international interchange of professional knowledge, information, and education in communication sciences and disorders is a means to strengthen research collaboration and improve services. ASHA has provided a resource for evidence-based research via the Practice Portal.

The scope of practice in speech-language pathology comprises five domains of professional practice and eight domains of service delivery.

Professional practice domains:

- advocacy and outreach

- supervision

- education

- administration/leadership

- research

Service delivery domains

- Collaboration

- Counseling

- Prevention and Wellness

- Screening

- Assessment

- Treatment

- Modalities, Technology, and Instrumentation

- Population and Systems

SLPs provide services to individuals with a wide variety of speech, language, and swallowing differences and disorders within the above-mentioned domains that range in function from completely intact to completely compromised. The diagnostic categories in the speech-language pathology scope of practice are consistent with relevant diagnostic categories under the WHO's (2014) ICF, the American Psychiatric Association's (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the categories of disability under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 2004 (see also U.S. Department of Education, 2004), and those defined by two semiautonomous bodies of ASHA: the Council on Academic Accreditation in Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology and the Council for Clinical Certification in Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology.

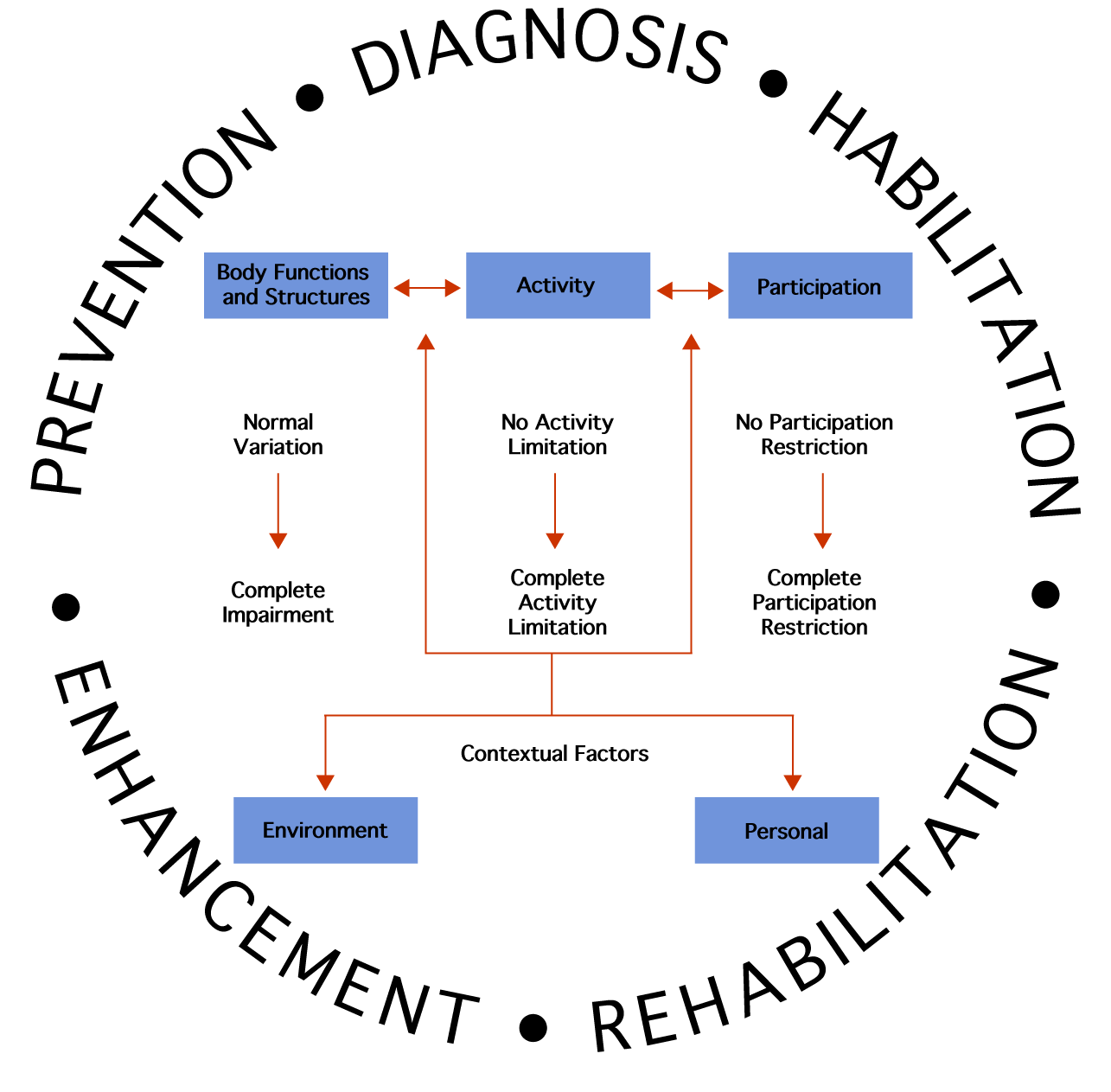

The domains of speech-language pathology service delivery complement the ICF, the WHO's multipurpose health classification system (WHO, 2014). The classification system provides a standard language and framework for the description of functioning and health. The ICF framework is useful in describing the breadth of the role of the SLP in the prevention, assessment, and habilitation/rehabilitation of communication and swallowing disorders and the enhancement and scientific investigation of those functions. The framework consists of two components: health conditions and contextual factors.

Health Conditions

Body Functions and Structures: These involve the anatomy and physiology of the human body. Relevant examples in speech-language pathology include craniofacial anomaly, vocal fold paralysis, cerebral palsy, stuttering, and language impairment.

Activity and Participation: Activity refers to the execution of a task or action. Participation is the involvement in a life situation. Relevant examples in speech-language pathology include difficulties with swallowing safely for independent feeding, participating actively in class, understanding a medical prescription, and accessing the general education curriculum.

Contextual Factors

Environmental Factors: These make up the physical, social, and attitudinal environments in which people live and conduct their lives. Relevant examples in speech-language pathology include the role of the communication partner in augmentative and alternative communication (AAC), the influence of classroom acoustics on communication, and the impact of institutional dining environments on individuals' ability to safely maintain nutrition and hydration.

Personal Factors: These are the internal influences on an individual's functioning and disability and are not part of the health condition. Personal factors may include, but are not limited to, age, gender, ethnicity, educational level, social background, and profession. Relevant examples in speech-language pathology might include an individual's background or culture, if one or both influence his or her reaction to communication or swallowing.

The framework in speech-language pathology encompasses these health conditions and contextual factors across individuals and populations. Figure 2 illustrates the interaction of the various components of the ICF. The health condition component is expressed on a continuum of functioning. On one end of the continuum is intact functioning; at the opposite end of the continuum is completely compromised function. The contextual factors interact with each other and with the health conditions and may serve as facilitators or barriers to functioning. SLPs influence contextual factors through education and advocacy efforts at local, state, and national levels.

Figure 2. Interaction of the various components of the ICF model. This model applies to individuals or groups.

Domains of Speech-Language Pathology Service Delivery

The eight domains of speech-language pathology service delivery are collaboration; counseling; prevention and wellness; screening; assessment; treatment; modalities, technology, and instrumentation; and population and systems.

Collaboration

SLPs share responsibility with other professionals for creating a collaborative culture. Collaboration requires joint communication and shared decision making among all members of the team, including the individual and family, to accomplish improved service delivery and functional outcomes for the individuals served. When discussing specific roles of team members, professionals are ethically and legally obligated to determine whether they have the knowledge and skills necessary to perform such services. Collaboration occurs across all speech-language pathology practice domains.

As our global society is becoming more connected, integrated, and interdependent, SLPs have access to a variety of resources, information technology, diverse perspectives and influences (see, e.g., Lipinsky, Lombardo, Dominy, & Feeney, 1997). Increased national and international interchange of professional knowledge, information, and education in communication sciences and disorders is a means to strengthen research collaboration and improve services. SLPs

- educate stakeholders regarding interprofessional education (IPE) and interprofessional practice (IPP) (ASHA, 2014) principles and competencies;

- partner with other professions/organizations to enhance the value of speech-language pathology services;

- share responsibilities to achieve functional outcomes;

- consult with other professionals to meet the needs of individuals with communication and swallowing disorders;

- serve as case managers, service delivery coordinators, members of collaborative and patient care conference teams; and

- serve on early intervention and school pre-referral and intervention teams to assist with the development and implementation of individualized family service plans (IFSPs) and individualized education programs (IEPs).

Counseling

SLPs counsel by providing education, guidance, and support. Individuals, their families and their caregivers are counseled regarding acceptance, adaptation, and decision making about communication, feeding and swallowing, and related disorders. The role of the SLP in the counseling process includes interactions related to emotional reactions, thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that result from living with the communication disorder, feeding and swallowing disorder, or related disorders.

SLPs engage in the following activities in counseling persons with communication and feeding and swallowing disorders and their families:

- empower the individual and family to make informed decisions related to communication or feeding and swallowing issues.

- educate the individual, family, and related community members about communication or feeding and swallowing disorders.

- provide support and/or peer-to-peer groups for individuals with disorders and their families.

- provide individuals and families with skills that enable them to become self-advocates.

- discuss, evaluate, and address negative emotions and thoughts related to communication or feeding and swallowing disorders.

- refer individuals with disorders to other professionals when counseling needs fall outside of those related to (a) communication and (b) feeding and swallowing.

Prevention and Wellness

SLPs are involved in prevention and wellness activities that are geared toward reducing the incidence of a new disorder or disease, identifying disorders at an early stage, and decreasing the severity or impact of a disability associated with an existing disorder or disease. Involvement is directed toward individuals who are vulnerable or at risk for limited participation in communication, hearing, feeding and swallowing, and related abilities. Activities are directed toward enhancing or improving general well-being and quality of life. Education efforts focus on identifying and increasing awareness of risk behaviors that lead to communication disorders and feeding and swallowing problems. SLPs promote programs to increase public awareness, which are aimed at positively changing behaviors or attitudes.

Effective prevention programs are often community based and enable the SLP to help reduce the incidence of spoken and written communication and swallowing disorders as a public health and public education concern.

Examples of prevention and wellness programs include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Language impairment: Educate parents, teachers and other school-based professionals about the clinical markers of language impairment and the ways in which these impairments can impact a student's reading and writing skills to facilitate early referral for evaluation and assessment services.

- Language-based literacy disorders: Educate parents, school personnel, and health care providers about the SLP's role in addressing the semantic, syntactic, morphological, and phonological aspects of literacy disorders across the lifespan.

- Feeding: Educate parents of infants at risk for feeding problems about techniques to minimize long-term feeding challenges.

- Stroke prevention: Educate individuals about risk factors associated with stroke

- Serve on teams: Participate on multitiered systems of support (MTSS)/response to intervention (RTI) teams to help students successfully communicate within academic, classroom, and social settings.

- Fluency: Educate parents about risk factors associated with early stuttering.

- Early childhood: Encourage parents to participate in early screening and to collaborate with physicians, educators, child care providers, and others to recognize warning signs of developmental disorders during routine wellness checks and to promote healthy communication development practices.

- Prenatal care: Educate parents to decrease the incidence of speech, hearing, feeding and swallowing, and related disorders due to problems during pregnancy.

- Genetic counseling: Refer individuals to appropriate professionals and professional services if there is a concern or need for genetic counseling.

- Environmental change: Modify environments to decrease the risk of occurrence (e.g., decrease noise exposure).

- Vocal hygiene: Target prevention of voice disorders (e.g., encourage activities that minimize phonotrauma and the development of benign vocal fold pathology and that curb the use of smoking and smokeless tobacco products).

- Hearing: Educate individuals about risk factors associated with noise-induced hearing loss and preventive measures that may help to decrease the risk.

- Concussion /traumatic brain injury awareness: Educate parents of children involved in contact sports about the risk of concussion.

- Accent/dialect modification: Address sound pronunciation, stress, rhythm, and intonation of speech to enhance effective communication.

- Transgender (TG) and transsexual (TS) voice and communication: Educate and treat individuals about appropriate verbal, nonverbal, and voice characteristics (feminization or masculinization) that are congruent with their targeted gender identity.

- Business communication: Educate individuals about the importance of effective business communication, including oral, written, and interpersonal communication.

- Swallowing: Educate individuals who are at risk for aspiration about oral hygiene techniques.

Screening

SLPs are experts at screening individuals for possible communication, hearing, and/or feeding and swallowing disorders. SLPs have the knowledge of-and skills to treat-these disorders; they can design and implement effective screening programs and make appropriate referrals. These screenings facilitate referral for appropriate follow-up in a timely and cost-effective manner. SLPs

- select and use appropriate screening instrumentation;

- develop screening procedures and tools based on existing evidence;

- coordinate and conduct screening programs in a wide variety of educational, community, and health care settings;

- participate in public school MTSS/RTI team meetings to review data and recommend interventions to satisfy federal and state requirements (e.g., Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004 [IDEIA] and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973);

- review and analyze records (e.g., educational, medical);

- review, analyze, and make appropriate referrals based on results of screenings;

- consult with others about the results of screenings conducted by other professionals; and

- utilize data to inform decisions about the health of populations.

Assessment

Speech-language pathologists have expertise in the differential diagnosis of disorders of communication and swallowing. Communication, speech, language, and swallowing disorders can occur developmentally, as part of a medical condition, or in isolation, without an apparent underlying medical condition. Competent SLPs can diagnose communication and swallowing disorders but do not differentially diagnose medical conditions. The assessment process utilizes the ICF framework, which includes evaluation of body function, structure, activity and participation, within the context of environmental and personal factors. The assessment process can include, but is not limited to, culturally and linguistically appropriate behavioral observation and standardized and/or criterion-referenced tools; use of instrumentation; review of records, case history, and prior test results; and interview of the individual and/or family to guide decision making. The assessment process can be carried out in collaboration with other professionals. SLPs

- administer standardized and/or criterion-referenced tools to compare individuals with their peers;

- review medical records to determine relevant health, medical, and pharmacological information;

- interview individuals and/or family to obtain case history to determine specific concerns;

- utilize culturally and linguistically appropriate assessment protocols;

- engage in behavioral observation to determine the individual's skills in a naturalistic setting/context;

- diagnose communication and swallowing disorders;

- use endoscopy, videofluoroscopy, and other instrumentation to assess aspects of voice, resonance, velopharyngeal function and swallowing;

- document assessment and trial results for selecting AAC interventions and technology, including speech-generating devices (SGDs);

- participate in meetings adhering to required federal and state laws and regulations (e.g., IDEIA [2004] and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973).

- document assessment results, including discharge planning;

- formulate impressions to develop a plan of treatment and recommendations; and

- discuss eligibility and criteria for dismissal from early intervention and school-based services.

Treatment

Speech-language services are designed to optimize individuals' ability to communicate and swallow, thereby improving quality of life. SLPs develop and implement treatment to address the presenting symptoms or concerns of a communication or swallowing problem or related functional issue. Treatment establishes a new skill or ability or remediates or restores an impaired skill or ability. The ultimate goal of therapy is to improve an individual's functional outcomes. To this end, SLPs

- design, implement, and document delivery of service in accordance with best available practice appropriate to the practice setting;

- provide culturally and linguistically appropriate services;

- integrate the highest quality available research evidence with practitioner expertise and individual preferences and values in establishing treatment goals;

- utilize treatment data to guide decisions and determine effectiveness of services;

- integrate academic materials and goals into treatment;

- deliver the appropriate frequency and intensity of treatment utilizing best available practice;

- engage in treatment activities that are within the scope of the professional's competence;

- utilize AAC performance data to guide clinical decisions and determine the effectiveness of treatment; and

- collaborate with other professionals in the delivery of services.

Modalities, Technology, and Instrumentation

SLPs use advanced instrumentation and technologies in the evaluation, management, and care of individuals with communication, feeding and swallowing, and related disorders. SLPs are also involved in the research and development of emerging technologies and apply their knowledge in the use of advanced instrumentation and technologies to enhance the quality of the services provided. Some examples of services that SLPs offer in this domain include, but are not limited to, the use of

- the full range of AAC technologies to help individuals who have impaired ability to communicate verbally on a consistent basis-AAC devices make it possible for many individuals to successfully communicate within their environment and community;

- endoscopy, videofluoroscopy, fiber-optic evaluation of swallowing (voice, velopharyngeal function, swallowing) and other instrumentation to assess aspects of voice, resonance, and swallowing;

- telehealth/telepractice to provide individuals with access to services or to provide access to a specialist;

- ultrasound and other biofeedback systems for individuals with speech sound production, voice, or swallowing disorders; and

- other modalities (e.g., American Sign Language), where appropriate.

Population and Systems

In addition to direct care responsibilities, SLPs have a role in (a) managing populations to improve overall health and education, (b) improving the experience of the individuals served, and, in some circumstances, (c) reducing the cost of care. SLPs also have a role in improving the efficiency and effectiveness of service delivery. SLPs serve in roles designed to meet the demands and expectations of a changing work environment. SLPs

- use plain language to facilitate clear communication for improved health and educationally relevant outcomes;

- collaborate with other professionals about improving communication with individuals who have communication challenges;

- improve the experience of care by analyzing and improving communication environments;

- reduce the cost of care by designing and implementing case management strategies that focus on function and by helping individuals reach their goals through a combination of direct intervention, supervision of and collaboration with other service providers, and engagement of the individual and family in self-management strategies;

- serve in roles designed to meet the demands and expectations of a changing work environment;

- contribute to the management of specific populations by enhancing communication between professionals and individuals served;

- coach families and early intervention providers about strategies and supports for facilitating prelinguistic and linguistic communication skills of infants and toddlers; and

- support and collaborate with classroom teachers to implement strategies for supporting student access to the curriculum.

Speech-Language Pathology Service Delivery Areas

This list of practice areas and the bulleted examples are not comprehensive. Current areas of practice, such as literacy, have continued to evolve, whereas other new areas of practice are emerging. Please refer to the ASHA Practice Portal for a more extensive list of practice areas.

Fluency

- Stuttering

- Cluttering

Speech Production

- Motor planning and execution

- Articulation

- Phonological

Language- Spoken and written language (listening, processing, speaking, reading, writing, pragmatics)

- Phonology

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Semantics

- Pragmatics (language use and social aspects of communication)

- Prelinguistic communication (e.g., joint attention, intentionality, communicative signaling)

- Paralinguistic communication (e.g., gestures, signs, body language)

- Literacy (reading, writing, spelling)

Cognition

- Attention

- Memory

- Problem solving

- Executive functioning

Voice

- Phonation quality

- Pitch

- Loudness

- Alaryngeal voice

Resonance

- Hypernasality

- Hyponasality

- Cul-de-sac resonance

- Forward focus

Feeding and Swallowing

- Oral phase

- Pharyngeal phase

- Esophageal phase

- Atypical eating (e.g., food selectivity/refusal, negative physiologic response)

Auditory Habilitation/Rehabilitation

- Speech, language, communication, and listening skills impacted by hearing loss, deafness

- Auditory processing

Potential etiologies of communication and swallowing disorders include

- neonatal problems (e.g., prematurity, low birth weight, substance exposure);

- developmental disabilities (e.g., specific language impairment, autism spectrum disorder, dyslexia, learning disabilities, attention-deficit disorder, intellectual disabilities, unspecified neurodevelopmental disorders);

- disorders of aerodigestive tract function (e.g., irritable larynx, chronic cough, abnormal respiratory patterns or airway protection, paradoxical vocal fold motion, tracheostomy);

- oral anomalies (e.g., cleft lip/palate, dental malocclusion, macroglossia, oral motor dysfunction);

- respiratory patterns and compromise (e.g., bronchopulmonary dysplasia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease);

- pharyngeal anomalies (e.g., upper airway obstruction, velopharyngeal insufficiency/incompetence);

- laryngeal anomalies (e.g., vocal fold pathology, tracheal stenosis);

- neurological disease/dysfunction (e.g., traumatic brain injury, cerebral palsy, cerebrovascular accident, dementia, Parkinson's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis);

- psychiatric disorder (e.g., psychosis, schizophrenia);

- genetic disorders (e.g., Down syndrome, fragile X syndrome, Rett syndrome, velocardiofacial syndrome); and

- Orofacial myofunctional disorders (e.g., habitual open-mouth posture/nasal breathing, orofacial habits, tethered oral tissues, chewing and chewing muscles, lips and tongue resting position).

This list of etiologies is not comprehensive.

Elective services include

- Transgender communication (e.g., voice, verbal and nonverbal communication);

- Preventive vocal hygiene;

- Business communication;

- Accent/dialect modification; and

- Professional voice use.

This list of elective services is not comprehensive.

Domains of Professional Practice

This section delineates the domains of professional practice-that is, a set of skills and knowledge that goes beyond clinical practice. The domains of professional practice include advocacy and outreach, supervision, education, research, and administration and leadership.

Advocacy and Outreach

SLPs advocate for the discipline and for individuals through a variety of mechanisms, including community awareness, prevention activities, health literacy, academic literacy, education, political action, and training programs. Advocacy promotes and facilitates access to communication, including the reduction of societal, cultural, and linguistic barriers. SLPs perform a variety of activities, including the following:

- Advise regulatory and legislative agencies about the continuum of care. Examples of service delivery options across the continuum of care include telehealth/telepractice, the use of technology, the use of support personnel, and practicing at the top of the license.

- Engage decision makers at the local, state, and national levels for improved administrative and governmental policies affecting access to services and funding for communication and swallowing issues.

- Advocate at the local, state, and national levels for funding for services, education, and research.

- Participate in associations and organizations to advance the speech-language pathology profession.

- Promote and market professional services.

- Help to recruit and retain SLPs with diverse backgrounds and interests.

- Collaborate on advocacy objectives with other professionals/colleagues regarding mutual goals.

- Serve as expert witnesses, when appropriate.

- Educate consumers about communication disorders and speech-language pathology services.

- Advocate for fair and equitable services for all individuals, especially the most vulnerable.

- Inform state education agencies and local school districts about the various roles and responsibilities of school-based SLPs, including direct service, IEP development, Medicaid billing, planning and delivery of assessment and therapy, consultation with other team members, and attendance at required meetings.

Supervision

Supervision is a distinct area of practice; is the responsibility of SLPs; and crosses clinical, administrative, and technical spheres. SLPs are responsible for supervising Clinical Fellows, graduate externs, trainees, speech-language pathology assistants, and other personnel (e.g., clerical, technical, and other administrative support staff). SLPs may also supervise colleagues and peers. SLPs acknowledge that supervision is integral in the delivery of communication and swallowing services and advances the discipline. Supervision involves education, mentorship, encouragement, counseling, and support across all supervisory roles. SLPs

- possess service delivery and professional practice skills necessary to guide the supervisee;

- apply the art and science of supervision to all stakeholders (i.e., those supervising and being supervised), recognizing that supervision contributes to efficiency in the workplace;

- seek advanced knowledge in the practice of effective supervision;

- establish supervisory relationships that are collegial in nature;

- support supervisees as they learn to handle emotional reactions that may affect the therapeutic process; and

- establish a supervisory relationship that promotes growth and independence while providing support and guidance.

Education

SLPs serve as educators, teaching students in academic institutions and teaching professionals through continuing education in professional development formats. This more formal teaching is in addition to the education that SLPs provide to individuals, families, caregivers, decision makers, and policy makers, which is described in other domains. SLPs

- serve as faculty at institutions of higher education, teaching courses at the undergraduate, graduate, and postgraduate levels;

- mentor students who are completing academic programs at all levels;

- provide academic training to students in related disciplines and students who are training to become speech-language pathology assistants; and

- provide continuing professional education to SLPs and to professionals in related disciplines.

Research

SLPs conduct and participate in basic and applied/translational research related to cognition, verbal and nonverbal communication, pragmatics, literacy (reading, writing and spelling), and feeding and swallowing. This research may be undertaken as a facility-specific effort or may be coordinated across multiple settings. SLPs engage in activities to ensure compliance with Institutional Review Boards and international laws pertaining to research. SLPs also collaborate with other researchers and may pursue research funding through grants.

Administration and Leadership

SLPs administer programs in education, higher education, schools, health care, private practice, and other settings. In this capacity, they are responsible for making administrative decisions related to fiscal and personnel management; leadership; program design; program growth and innovation; professional development; compliance with laws and regulations; and cooperation with outside agencies in education and healthcare. Their administrative roles are not limited to speech-language pathology, as they may administer programs across departments and at different levels within an institution. In addition, SLPs promote effective and manageable workloads in school settings, provide appropriate services under IDEIA (2004), and engage in program design and development.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2005). Evidence-based practice in communication disorders [Position statement]. Available from www.asha.org/policy/.

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2014). Interprofessional education/interprofessional practice (IPE/IPP). Available from www.asha.org/practice/ipe-ipp/

Bridges, D. R., Davidson, R. A., Odegard, P. S., Maki, I. V., & Tomkowiak, J. (2011). Interprofessional collaboration: Three best practice models of interprofessional education. Medical Education Online, 16. doi:10.3402/meo.v16i0.6035. Retrieved from www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3081249/

Craddock, D., O'Halloran, C., Borthwick, A., & McPherson, K. (2006). Interprofessional education in health and social care: Fashion or informed practice? Learning in Health and Social Care, 5, 220-242. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1473-6861.2006.00135.x/abstract

Individuals With Disabilities Education Act of 2004, 20 U.S.C. § 1400 et seq. (2004).

Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004, 20 U.S.C. § 1400 et seq. (2004).

Lipinski, C. A., Lombardo, F., Dominy, B. W., & Feeney, P. J. (1997, March 1). Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 46(1-3), 3-26. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11259830

Rehabilitation Act of 1973, 29 U.S.C. § 701 et seq.

U.S. Department of Education. (2004). Building the legacy: IDEA 2004. Retrieved from http://idea.ed.gov/

World Health Organization. (2014). International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: Author. Retrieved from www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/

Resources

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (n.d.). Introduction to evidence-based practice. Retrieved from www.asha.org/Research/EBP/Evidence-Based-Practice/

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (n.d.). Practice Portal. Available from /practice-portal/

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (1991).A model for collaborative service delivery for students with language-learning disorders in the public schools [Paper]. Available from www.asha.org/policy/

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2003). Evaluating and treating communication and cognitive disorders: Approaches to referral and collaboration for speech-language pathology and clinical neuropsychology [Technical report]. Available from www.asha.org/policy/

Paul, D. (2013, August). A quick guide to DSM-V. The ASHA Leader, 18, 52-54. Retrieved from http://leader.pubs.asha.org/article.aspx?articleid=1785031

U.S. Department of Justice. (2009). A guide to disability rights laws. Retrieved from www.ada.gov/cguide.htm

Index terms: scope of practice

Reference this material as: American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2016). Scope of practice in speech-language pathology [Scope of Practice]. Available from www.asha.org/policy/.

© Copyright 2016 American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. All rights reserved.

Disclaimer: The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association disclaims any liability to any party for the accuracy, completeness, or availability of these documents, or for any damages arising out of the use of the documents and any information they contain.

doi:10.1044/policy.SP2016-00343